A drawn out affair

Acclaimed cartoonist Tony Husband and his former heroin addict son Paul say why their book From A Dark Place has lighter moments

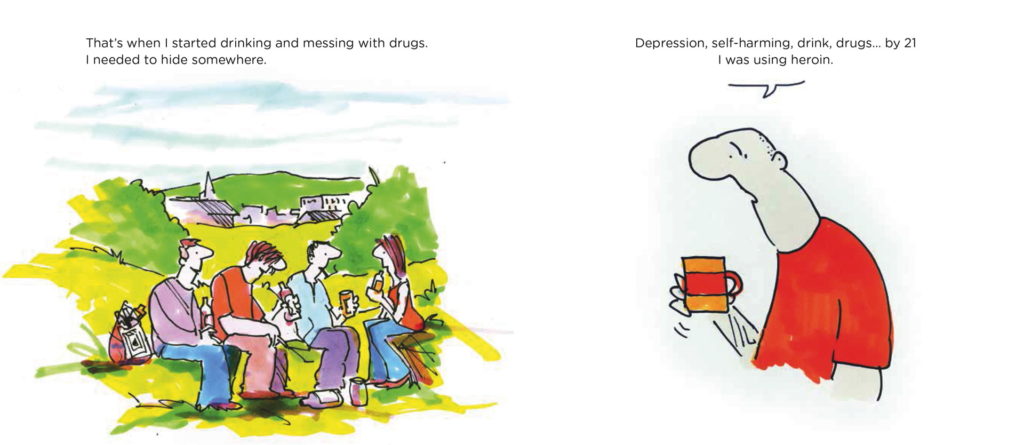

It’s no mean feat to transform the complexity and trauma of heroin addiction into a 50-page book of cartoons. Addiction can tear families apart in months, destroy careers and terminate relationships with friends and loved ones, but for Tony Husband and his son Paul, it is important to show that it can be overcome.

Tony has been a cartoonist for Private Eye and The Times, among other publications, for over 30 years, winning numerous awards for the powerful simplicity, wit and character of his drawings. Three years ago, he decided to try something new. His father had just died of dementia and he had to find a way to deal with the loss that wouldn’t affect his work. So he drew it. These drawings turned into his first “serious” book, Take Care Son, titled after the last words his dad said to him before he died.

The success of this book went beyond what he had imagined: it is used now in care homes to help nurses and carers understand the experience of Alzheimer’s and how to cope with it. Now Tony travels the country delivering talks on the topic – talks in which audience members are just as likely to laugh as cry.

So when he approached his son Paul to write a second book of similar style, this time on their combined journey through Paul’s addiction towards ultimate recovery, Paul was able to see instantly the importance it could have for people going through similar experiences, both as addicts and parents.

“You don’t hear a lot of stories about addiction that have positive endings,” Paul observes, speaking at his father’s house in Hyde, Tameside. “Especially when they’re written by parents of drug users, because it tends to be that they’ve written the book because their child has died.”

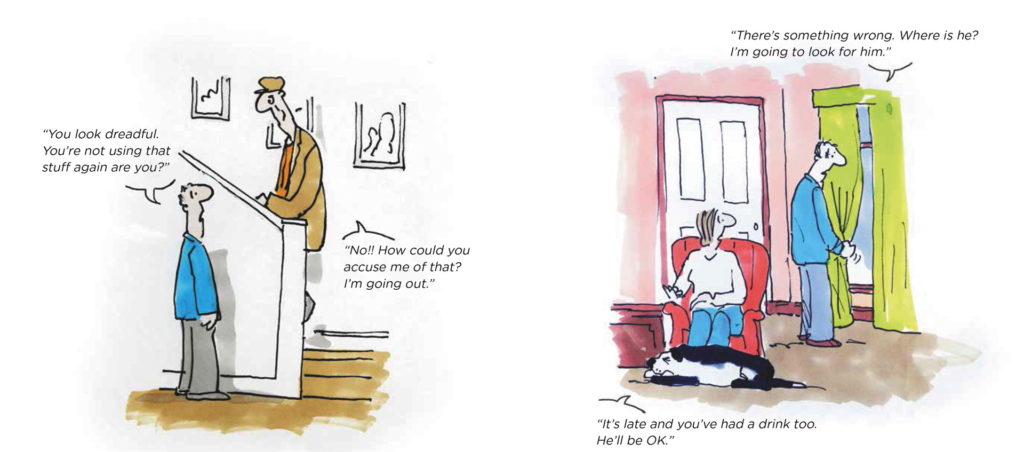

Despite the happy ending to Paul’s story, it was a difficult writing experience for both father and son. “There were lots of things I hadn’t known before,” Tony confesses. “Whenever he left the house, we didn’t know where he was or how bad it was. We could have guessed but, hearing it all these years later, it was hard.”

For Paul, there had been some expectation of catharsis from the process of writing, but ultimately the experience of revisiting his addiction in brutal honesty with his dad was an unpleasant one.

“I don’t know if there’s anything out there for parents – they’re always in the shadows.”

“I think we will reach a stage where we do find the whole experience cathartic, once we’ve passed this initial discomfort and it’s out there. But it’s not really for us. I hope it will help other people, parents specifically, because I don’t know if there’s anything out there for parents – they’re always in the shadows and nobody really speaks about them.

“The drug and alcohol services don’t do much to help the people around the addicts. Often they’ll just deal with the person that’s in front of them – give them a prescription or whatever – and they’re not interested in the echoes of chaos that have spread around them. A lot of people just don’t know how to deal with it.”

In the depths of Paul’s addiction, it was difficult for Tony to know what to do. His wife Carole had taken a hardline approach with Paul since he was a boy – not in a nasty way but strict with money – and so he would tend to go to his dad whenever he needed some.

“I’d become what you call an enabler,” Tony says with regret. “I didn’t realise at the time, but I was allowing him to carry on being an addict. It was hard because you don’t know how much of what he’s saying is the truth. The addict becomes a brilliant actor and liar, and as a parent you want to believe the lies, you want to believe that he’s getting help and getting better, but the reality was that when I was lending him £20 he was using it to score.”

There’s never a sense that Paul blames his father for any of his actions. He admits that an addict can become an accomplished deceiver, and he did. Paraphrasing Shaun Ryder he says: “If you were able to take that side of addiction, what you do to get the money, if you could hold onto that outside of addiction, you’d be rich.”

One of the primary intentions of the book is to promote sympathy for and understanding of addiction, which Tony and Paul believe is missing from much of society. “There’s a frequently held perception that addicts are just happy with their existence,” Paul explains. “But people don’t see how much self-loathing and anger there is.

“Nobody wants to be getting up at six o’clock every morning in absolute agony, rooting around for money, waiting on street corners for some scumbag dealer to drop off for you just so you can feel all right again. Nobody likes that. The amount of times I remember waking up in the morning and just really wishing that I’d not woken up.”

Tony believes that this cycle of addiction and self-loathing is only perpetuated by the drug and alcohol recovery services, and the manner in which they attempt to reintegrate addicts into society. “Often when you go to these meetings, they make you feel worthless – going to this rundown building with plastic chairs and peeling posters, glum faces all around and a receptionist behind a glass panel and outside you’ve got people dealing. Of course you’re going to feel: ‘This is what I’m worth, this is what society gives me to get better.’ Addicts need to feel like they are being welcomed back by society.”

This is where the Lancashire User Forum (LUF) excelled for Paul. It changed his mindset of not being good enough and instead motivated him to change for the better. Inspired by friends from the forum, he soon took up photography, a talent that had been suppressed during his addiction, and then after some time of recovery he met Sarah at a school reunion – the first girl he had ever fancied from primary school and now his wife and mother of his two daughters.

Tony says: “It’s an inspiring story really – that you can be down there, where Paul was, and reach the point he’s reached, with a lovely family, a major talent, respected as a photographer and as a father. The message is hope. That’s what I wanted from the book and I think that’s what we’ve got.”

Paul knows he was lucky that the LUF was able to come and help him at the time it did. In his opinion, not enough is being done by the drug and alcohol services to assist addicts, to seek them out and give them the push towards recovery they need.

“If you walk through Manchester now, the homeless situation is worse that I’ve ever seen it, and I know for a fact that a majority of those people have got drug or alcohol problems. They get religious groups coming up to them, but a lot of them aren’t going to go for that. We need the services going out and saying: ‘This is what we can do for you so come on, let’s go and do it now’. They really have to be pro-active about it.”

The project has taught both father and son the power of positivity and tenderness when dealing with addiction. “So much of the literature about addiction is too grim, too heavy,” says Tony. “But with this, there’s a gentleness about the cartoons. It’s a comfortable way of understanding things and we hope people can relate to the way we’ve told Paul’s story.”

Although their book takes just a few minutes to read, their hope is that it can have an impact on the way families cope with addiction, and assist more people to find that same ladder to recovery as Paul.

From a Dark Place: How A Family Coped with Drug Addiction by Tony Husband and Paul Husband is published by Robinson on 9 February (£8.99 in paperback, also available as an eBook) Main photo: Shay Rowan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.