Spell it out

Witches have been variously feared, burnt, respected and celebrated through history. With Halloween approaching, Antonia Charlesworth asks what our depiction of these magical figures says about us

Halloween costumes are becoming increasingly elaborate, with endless options available to anyone who has a makeup kit, a Pinterest board and a spare month to practise. If you’ve left it to the last minute, however, you’ll find no shortage of readymade costumes online or in your local supermarket. But, if you’re female, you may struggle to find anything genuinely frightening.

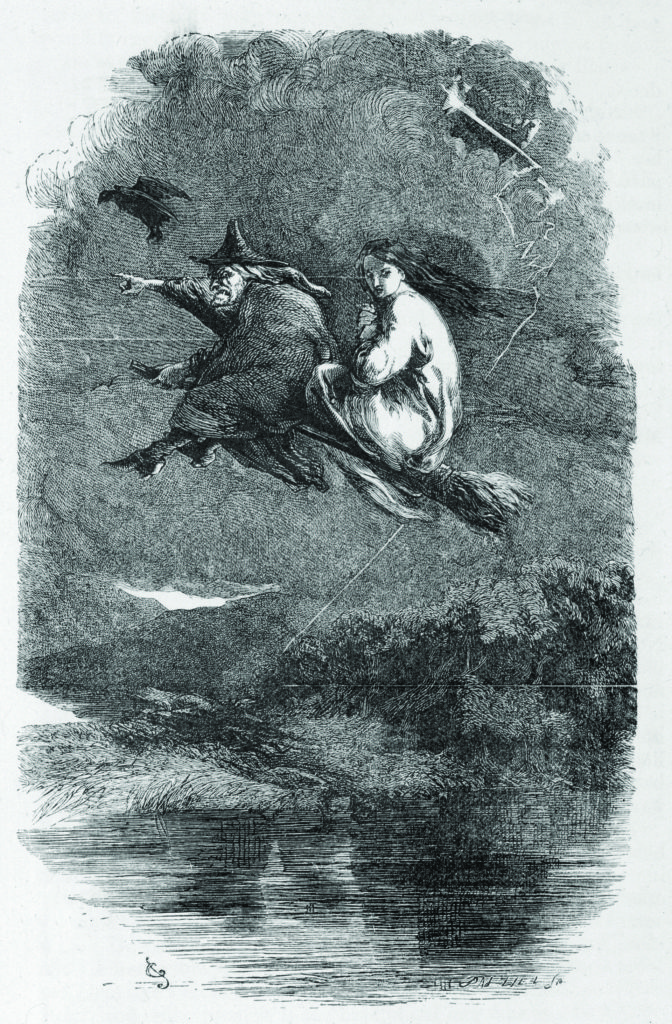

Last year online retailer Amazon was forced to pull a range of hyper-sexualised Halloween costumes for girls as young as four from its online marketplace – an extreme example of the increasing sexification of the spooky holiday. A fearsome, hook-nosed, broomstick-riding hag happily still offers respite, but for every scary witch costume there is an array of sexy enchantress costumes available too.

“What’s really disturbing about the hag is when she becomes sexual.”

Far from originating in student Halloween bar crawls, the sexualised witch can be identified as early as 1486 when Heinrich Kramer, a German Catholic clergyman, wrote The Malleus Maleficarum – a handbook for witch hunters.

The Malleus explains that witchcraft is a woman’s crime because woman is “more carnal than man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations… witchcraft came from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable”.

The charges levied against these insatiable women included making men’s genitals disappear, or stealing them – keeping them in nests or boxes and feeding them oats and corn. This, wrote Kramer before providing detailed methods to catch the temptresses, was a matter of common report. Far from being written off as the god-fearing, woman-hating crackpot he clearly was, Kramer gained a bit of a following. An estimated 40,000-60,000 people were executed during the witch trials of the early modern period. Of course they weren’t all women – only around 85 per cent.

Execution by burning – evoking hellfire and flames of passion – was deemed appropriate punishment for such crimes. In Europe it was the preferred way to kill a witch because it was more painful. The confessions that led up to it were often elicited through sexually humiliating torture techniques such as, in Italy, being forced to sit on red-hot stools so that the accused woman would not be able to perform sexual acts with the devil.

“The image of the burning witch is very symbolic, particularly for people at that time who would have believed in hell and eternal flames,” says Lancaster University academic Catherine Spooner, an expert on witches. “It’s representing that in a very physical and literal way and it retains its power now.”

It’s easy to see why modern feminism claimed the witches as its martyrs. Matilda Joslyn Gage, a writer involved in the suffrage movement, published a book in 1893 that claimed witches were pagan priestesses worshipping the Great Goddess. In 1973 second wave feminists Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English put forward in a pamphlet the idea that the persecuted women were traditional healers and midwives.

“The witch became very important for feminists from the sixties and seventies, right up until now,” says Spooner. “It became a story in which a lot of other concerns could be addressed, about marginalisation, exclusion and persecution.”

Both publications implied that the witches were a threat to the patriarchal institutions of the church and what passed for orthodox medicine, and were brought down accordingly. But both used the inflated claim that there were nine million victims of the witch trials – an estimate made by German scholar Gottfried Christian Voigt in 1784 – and so have been condemned because of historical inaccuracy.

In conservative England and later in New England during the Salem witch trials of 1692-1693, hanging was preferred to burning. “The burning witch is not accurate of England at all,” says Spooner. “It was a Protestant country and that was not considered humane… Witchcraft is represented differently in different countries so while on the Continent it was much more sexualised, representations in Britain were not at all.”

Witches in England are characterised by the other type of Halloween costume you’ll find on the shelves – with the pointy hat, broomstick and warty hooked-nose – the hag. At the centre of the Pendle Witch covens tried in 1612 were two elderly widows in their seventies – Anne Whittle (aka Chattox) and Elizabeth Southerns (aka Demdike), who, lame and blind, appear to come straight from the pages of a fairytale.

The representations of the witch as sexy and haglike are two sides of the same coin, metaphors for the two things society, both then and now, fears most in women – sexual liberation and ageing.

“What’s really disturbing about the hag is when she becomes sexual and when the sexy one loses her youth she becomes the hag,” says Spooner. “The sexy one can be recuperated by patriarchal culture – why wouldn’t it like a sexy witch? But when the hag becomes sexy then that becomes threatening.”

Uneducated and poor, Chattox and Demdike were most likely wisewomen, common in isolated village life, making small sums as healers, using charms or ointments when doctors were not readily available. It’s safe to assume that if they, and their neighbours, believed they had powers for good they would also believe those powers could be used for hexes and wrongdoing against those who aggrieved them.

Spooner points out that these women became an obvious scapegoat during a time of religious and political upheaveal. In remote areas like Pendle, Catholics continued to practise openly during the English Reformation and stories from the town soon reached King James I, who had two intense interests – Protestant theology and, after a visit to Denmark where he’d attended a witch trial, witch hunting. His book Daemonologie instructed his followers that they must prosecute any practitioners and in his native Scotland witch hunting reached far more brutal extremes.

“Society chooses who it wants to exclude and it finds reasons to exclude them,” says Spooner. “To shore up their sense of self and consolidate their own identity, societies have to reject certain things – throw them off. So to deal with the social pressures that were fermenting at that time they had to pick someone – dirty people outside of the community – that they could get rid of to bolster their own strength. It was arbitrary – it could have been anyone – but it was useful that those women were there and already were the object of social tensions.”

One of the arguments against feminist interpretations of the witch trials is that women were often the accusers. But if Chattox and Demdike were both local wisewomen, poor and marginalised and in competition, it is logical that they would be ready to accuse one another when the witch hunters began paying attention to Pendle. Their competition ultimately led to each other’s, and the their associates’ demise.

In addition to duplicity among the Lancashire witches many believe they were coerced into confessions. Starved and sleep deprived, when stood before a court they ended up saying what they thought they were supposed to. But although that fits with the picture of the witch as oppressed victim, Spooner feels this isn’t how we should remember them.

“We shouldn’t get rid of the evil witch completely because for many of those women that is how they thought of themselves. If you take that away from them then they don’t have anything – that was their way of reclaiming some power in horrible circumstances. You can see from some of the confessions there’s a real sense of enjoyment in it, like: ‘Right, I’m just going to make up the most extravagant thing I can think of. Yes! I am going to ride off on a black beast!’”

In 2012 Spooner was involved in the 400th anniversary of the Lancashire witch trials. She was surprised to find how live this history remains in Lancaster, where the executions took place.

“Some people would want to merchandise it – sell pointy hats and brooms – and others just said: ‘No. Absolutely not. This is not appropriate, people died, they were real people who were executed as a miscarriage of justice and we have to be sensitive and respect that.’” Should we be paying similar respect to the victims of the witch trials on Halloween – ditch our stripy stockings and get practising our Pinterest make-up?

“I think Halloween is slightly different because it’s not linked to a particular event or specific set of historical circumstances. I love Halloween. There’s something celebratory and joyful about it that we shouldn’t ignore. That in itself can be positive and even political.

“It’s a chance to raise up social fears and deal with them in a way that is comfortable. We can enjoy being scared, but it’s not really scary. It’s innocence, it’s letting off steam and that forms a really valuable social function.”

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.